The Ground is Lava CS 175 - Project in AI (in Minecraft)

Project Summary

We are creating an agent that learns to solve simple mazes that are constructed from dirt blocks over a floor of lava, with a single lapis block marking the “goal block.” The agent’s percepts are highly limited (essentially blind at the moment) and is forced to gain its knowledge by iterating through multiple episodes of success and failure through the mazes. After numerous episodes, the agent learns the sequence of actions that will return the highest reward which is equivalent to reaching the goal block. The mazes are generated randomly using an algorithm that typically makes them difficult to solve.

Approach

Most of the code is in “sarsaattempt1.py.” Our agent uses the State-Action-Reward-State-Action (Sarsa) algorithm to learn the Markov Decision Process (MDP) policy. The MDP is simple and comparable to a gridworld. Each state is a position on the grid of the maze and is represented as a tuple of integers (which are in the form (int+0.5, int+0.5) in the actual code). A state can transition to another state by moving one block on the grid in any of the four directions: north, west, east or south. A move in any of these directions are the only allowable actions, so each action is in the form “move____ 1” (i.e. strings, which are discrete malmo movement commands). An episode in the MDP ends when the agent reaches the goal block or dies. Thus, the agent in “blind”, similiar to the cliff-walking example in tutorial_6.py of the Malmo tutorial. In other words, the agent does not have any field of vision and does not know if there is a goal state. However, the mazes that our agent can solve are more difficult than the cliff-walking example of tutorial_6.py (More on the maze generation later). We measured our agent’s performance by the number of episodes it takes to “converge” (see the “Evaluation” section).

We maintain a table of Q values for each visited state (adding new states to the table as we discover them) and use the Sarsa algorithm to update the Q values at every time step:

Q(s,a) = Q(s,a) + alpha(r + gammaQ(s’, a’) - Q(s, a))

s’ and a’ are the state arrived at by taking action a from s, and a’ is the action chosen from state s’ (using an epsilon greedy policy. More on that later). alpha is the learning rate (currently set to 0.8 in the code), r is the reward obtained from a state, and gamma is the discount factor (currently set to 0.9 in the code). We give an obligatory -2 reward for any action (so it is discouraged to just roam around), -100 reward for touching lava, and 1000000000 reward for touching the goal (lapis) block (This is all in “sarsaattempt1.xml”). As you can see in the video, once it finds the goal once, it’s very quick to converge.

An important “heuristic” we added for the agent was to not only discount states by the number of timesteps (which is what gamma does) but by the distance from the start state. We divide the reward obtained from a state s by the “Manhattan distance” of s from the start state (See: https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Manhattan_distance). This encourages the agent to move away from the start state, as dying further away from the start state is “better” than dying close to it. And since the goal is the furthest block away from the start in the mazes we generate, this discounting implicitly encourages the agent to “find” the goal. This is why in the video, it looks like the agent is getting “closer” to the goal as episodes go on.

We use an epsilon greedy policy to choose actions (with probability epsilon, pick a random action, otherwise pick the action with the best Q value from the given state), but with variable epsilon. Specifically, for a state s, we let epsilon = 1/N(s) where N(s) = The number of times s has been visited. This way, it is less confident about its action-value estimation on new states, but confident about states that it has visited many times. Actually, more specfically, at “forks in the road” on the maze, it will try all “forks” quite evenly (a good thing, in our opinion), since all appear to give it negative reward, so the Q values for those forks fluctuate. One possible reason for this is our high learning rate alpha, which causes it to accumulate (negative) rewards for a given state quickly, thus causing it to “change its mind” quickly. So even when epsilon is low, there is plenty of exploration through the maze thanks to the fluctuating Q values. The low epsilon on these states are not immaterial, however, as this is what prevents it from falling into the lava. Thus, it ends up only exploring “safe” directions, as desired.

On the maze generation: We implemented the a randomized Prim-Jarnik minimum spanning tree algorithm, as described here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maze_generation_algorithm#Randomized_Prim.27s_algorithm (The “Modified version”). The implementation is in “maze_gen2.py” (which is then called in the main sarsaaattempt1.py file) This is known to generate fairly difficult mazes. More specifically, it has a fairly high and uniform branching factor and–being an MST-based algorithm–does not allow cycles, so there is only a single possible path to every block (In particular, the goal block).

Evaluation

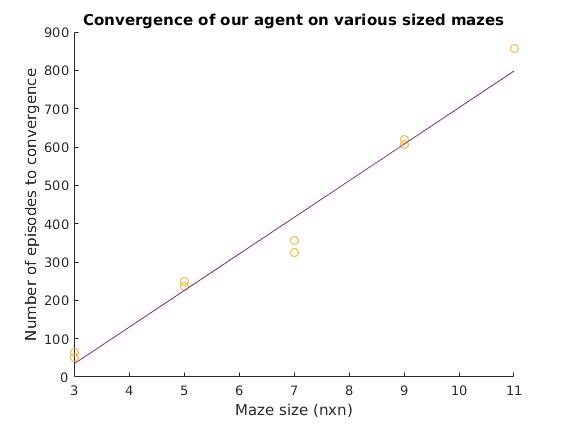

Our agent solves 3x3 mazes in about 50 episodes, 5x5 mazes in about 200 episodes, 7x7 mazes in about 350 episodes (The video shows a 7x7 maze), a 9x9 maze in about 600 episodes, and an 11x11 maze in about 900 episodes. When we say “solve the maze” we mean that it finds the goal state 3 times in a row (at that point, it is safe to assume that it more or less finds the goal state at every episode, though for larger mazes it takes slightly longer for the Q values near the goal to “propogate” back down the path). These estimates come from a few runs we did on each size, as depicted in the following graph:

We definitely completed our baseline (solving modestly small randomly generated mazes). Our agent is at a significant disadvantage compared to something like Dijkstra’s algorithm or a human player, as it is blind. But it certainly does better than a random agent (one that just pics actions uniformly), which cannot solve these mazes in a feasible amount of time (let alone find the goal state over and over).

A small technical detail is that there are some jerky episode restarts occurring in the middle of the maze (These are the random “pauses” the agent takes in the video). This doesn’t have any real effect on the algorithm other than overestimating the number of episodes it takes and causing it to move slightly slower, but it would be nice to have it go more smoothly.

Finally: The agent occasionally “cheats” in that if there’s a single gap between it and the goal block, it will just go into the gap and scrape the goal block before falling into the lava, reaping the reward before death, as doing so technically counts as “touching” the goal by malmo. Not sure if this is a feature or a bug.

Remaining Goals and Challenges

We want to perform a sufficient evaluation of our algorithm. It takes a long time for the agent to solve mazes, so we don’t have too much data on the number of episodes it takes (we only did about 2-3 runs on 8x8 and 10x10 mazes, and each time they took about 350 and 600 episodes respectively, which is how we got the Evaluation numbers, but we can’t be too sure about it). We also don’t have much to compare our agent against. Human players and direct maze solving algorithms (like Dijkstra’s) are too powerful in comparison to a blind agent, while a uniformly random agent is too weak.

On that note, perhaps our main next step is to test our original goal of giving the agent some percepts beyond its raw position, like a field of vision. Actually, if you look at the commit history, an earlier version of sarsaattempt1.py was experimenting with an MLPRegressor from scikit-learn to rate states by a 3x3 grid array from malmo (representing the blocks under the agent), which is an attempt to incorporate such a “field of vision”, but we temporarily removed it upon this progress report for the sake of simplicity. We might want to rollback to that version of the file and see whether it works better than the raw, blind Sarsa we’re currently using (we never really fully tested it). Some sort of helper heuristic function like this could help reduce the number of episodes it takes to converge (basically something better than the “Manhattan distance” discounting we’re currently using). Basically, we want to do “Sarsa+more sophisticated heuristic” rather than “Sarsa (+Manhattan distance).”

We also haven’t really tried it on larger mazes yet. Gathering data on that end of the spectrum might also be a goal (Gathering data in general is difficult for our project due to the time it takes).

We parenthetically noted in the Evaluation that it takes some time for the Q values to propogate back down a path. One way to speed this up (not just with regard to the goal state, but for any state) would be to incorporate eligibility traces into our algorithm, turning it into “Sarsa(lambda)” (see section 7.5 of the book) rather than just raw single-step Sarsa. This would give credit to earlier states for rewards found down the line. This is another, albeit lower priority, future idea for us (if we can’t manage to do the heuristic thing, this could be a fallback).

Video of Full Run

(Video is only of run due to time constraint).

Layout of specific maze in the video.

Mazes are randomly generated for each run using the Prim-Dijkstra algorithm.